History of Cloisonné

Cloisonné generally refers to the technique whereby a vitreous glaze is applied to a metal surface and then fired. Shippo-yaki, the Japanese word for cloisonné, means “seven treasures.” It refers to the seven treasures listed in the Lotus Sutra, which are gold, silver, lapis lazuli, giant clamshell, agate, pearl and carnelian. It is said that this name was given to cloisonné in Japan because it was as beautiful as these seven treasures.

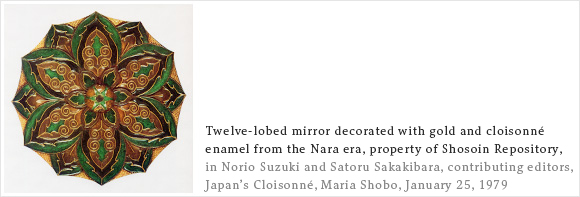

Cloisonné’s origins are quite ancient, dating back to more than three thousand years ago to the age characterized by King Tutankhamen’s golden mask. This art subsequently spread throughout Europe, and reached Japan in the sixth and seventh century via China and Korea. The oldest example of cloisonné in Japan is a mirror, the back of which is enameled with cloisonné. This mirror is now in the collection of the Shosoin, the repository of Imperial treasures in Nara.

Cloisonné production began to flourish in Japan in the 17th century. Donin Hirata of Kyoto learned the cloisonné technique from craftspersons from the Korean peninsula in the early Edo period.

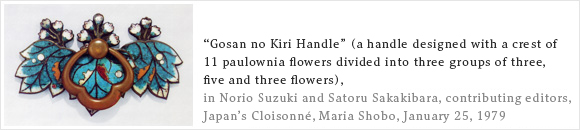

At this point in Japan’s history, cloisonné was used on sword fittings, as well as decoration on kugikakushi (an object that conceals the head of a nail) and sliding door pulls in castles, temples and shrines. However, the cloisonné technique was the closely-guarded secret of the Hirata family and was not shared with the general population.

In the latter half of the Edo period, Tsunekichi Kaji discovered the techniques of cloisonné on his own in the Owari region, heralding the start of “modern cloisonné). From this point, the production of cloisonné flourished in Owari, and it was recognized as a specialty of Owari in the Bakumatsu period (end of the Bakufu era).

This technique spread to Kanagawa Prefecture, Tokyo and Kyoto, remaining centered in the Owari region, to the extent that there was until recently a town named Shippo-cho (literally, “Town of the Seven Treasures”) in Aichi Prefecture whose name was derived from cloisonné.

Japan’s Cloisonné

Cloisonné plates are currently made in China as souvenirs, but this is the “doro shippo” (mud cloisonné) kind of cloisonné, which does not have the luster of glazing and looks opaque and flat. Doro shippo was the main type of cloisonné in Japan prior to the Meiji period (1868-1912).

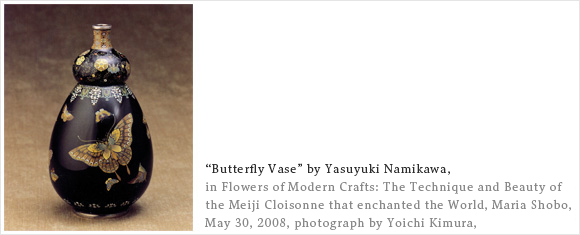

In the Meiji period, highly transparent glazes were developed in Japan, and Japan’s cloisonné art blossomed with the emergence of craftspersons such as Yasuyuki Namikawa and Sosuke Namikawa, who were appointed to the rank of Teishitsu Gigei-in (Imperial Household Artist). Japanese cloisonné received high commendation at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, receiving praise as a unique fine art form without precedent.

Subsequently, various new techniques were developed, particularly silver wire cloisonné. The cloisonné techniques that are currently used had all been developed by the end of the Meiji period, including the silver wire technique and cloisonné that focused on the groundwork materials.

The traditional techniques for making silver wire cloisonné grew even more sophisticated, requiring a higher level of technique and proficiency from the craftspersons. Japanese cloisonné reached its technical peak from the end of the Meiji period through the early Taisho period (1912-1926), as craftspersons produced work with the kind of extremely minute patterns and brilliant colors that are hard to reproduce today.

Thereafter, the cloisonné that was made for wealthy families and the Imperial court gained wide popularity as accessories for the common people.

Today, a wide range of cloisonné products are made, including flower vases and frames, Buddhist altar articles and accessories.

Owari Shippo (Cloisonné)

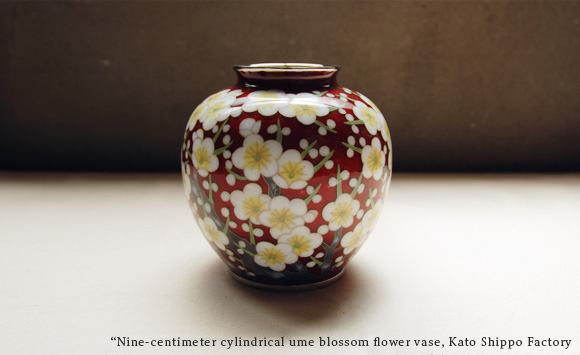

The cloisonné made primarily in Shippo-cho in Aichi Prefecture is known as “Owari Shippo.” It is grounded in the history and techniques developed by prior craftspersons, such as the traditional silver wire technique and the polishing technique.

Owari Shippo is the main type of cloisonné in Japan, started by Tsunekichi Kaji and passed down and developed through the present day. As part of this tradition, Katoshippo Works has carried on these ancient techniques passed down in the Nagoya region.

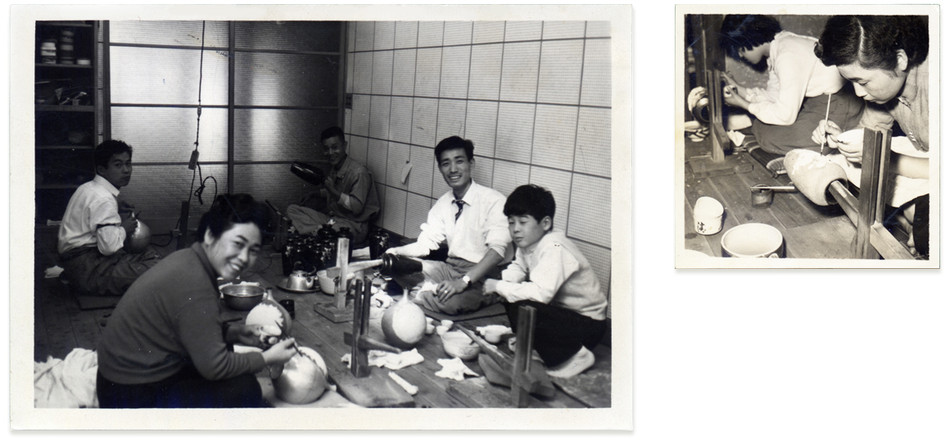

Katoshippo around 1955